Over the past several weeks I've had numerous calls from frustrated parents who have been engaged in some form of counseling or treatment with a teenage child where substance use was definitely part of the issue, but was not addressed responsibly by the professionals treating them:

- The mother of an 17-year-old boy stated she's aware that the boy is smoking marijuana—"probably every day"— so they've had him in counseling for that. The therapist did a substance use assessment and informed the parents the boy has a substance use disorder, but went on to say it's "mild," so he doesn't need anything more than what they're doing in their weekly counseling sessions. After a couple of months of feeling like no progress was being made, the mother expressed her concerns to the boy's psychiatrist, who suggested she call me.

- The mother of a 17-year-old called three weeks after the boy had completed an eight-week wilderness program. Substance use was clearly one of the reasons he had been placed in treatment. At the time she was calling, he was currently runaway, and back to using "some scary drugs." I asked what kind of plan was developed for continued management of his substance use disorder. "Not much." After watching a I video I gave her that talks about creating a solid foundation for recovery for treatment clients and avoiding potential cracks in the foundation, she sent me a text: "I feel deflated. We got none of that." They are currently trying to figure out how to afford to put him in another program.

- Parents of a 16-year-old girl contacted me when their daughter was towards the end of eight weeks in a PHP (day treatment) dual diagnosis treatment program. Substance use was identified as an issue going into the program. I asked the parents what the program was doing to address her substance use. Their response was, "They're teaching her coping skills for when she has urges." I asked if the program had ever talked with the parents about her Substance Use Disorder diagnosis. "No." On her first day back to school following treatment she got caught smoking marijuana on school grounds and was expelled.

These three examples would probably be a good place to stop as far creating a smooth flow for a blog post... But let me give you one more—just to drive home my point.

- The mother of a 17-year-old boy called after he had completed a 90-day dual diagnosis residential treatment program. He went back to smoking marijuana shortly after he completed the program. As I spoke with the mother about the importance of addressing substance use responsibly when it's part of a "dual" diagnosis, her response was "Thank you! That's what I've been feeling, but haven't been sure what to say about it." When I suggested that a "sort-of addressed issue" (in this case, the substance use) becomes an elephant in the room that ultimately causes problems with interpersonal relationships and family dynamics, she said, "Exactly! That's a really good way to put it." Things went off the rails very quickly and he's now back in another 90-day residential program.

Getting calls like this is nothing new to me. I've been watching parents go through the ordeal of addressing a substance use issue with their child, only to experience a poorly managed treatment effort that ultimately leads to tragic results for years now. It's why I sold my adolescent treatment program, wrote a book called Rehab Works! A Parent's Guide To Drug Treatment, and turned my attention to working specifically with parents to help them avoid these kind of scenarios.

But this latest spate of calls sort of got my dander up.

So I decided to do a talk—just go "live" and and have a frank conversation about some of these problems. I picked a date, figured out how to "livestream" (i.e. sit by yourself in an empty room and talk to a camera—agh!) and went for it. As a result of having a reason to organize my thoughts for the presentation, I was able to clarify some critical points I feel need to be talked about relative to addressing early stage substance use. I'll share some of those those points here, and will provide a link to the replay of the talk at the end of this article so you can watch the full presentation.

DEFINING THE PROBLEM

My first point was the simple fact that the problem starts when everybody's not on the same page as far as what it means to have a "problem."

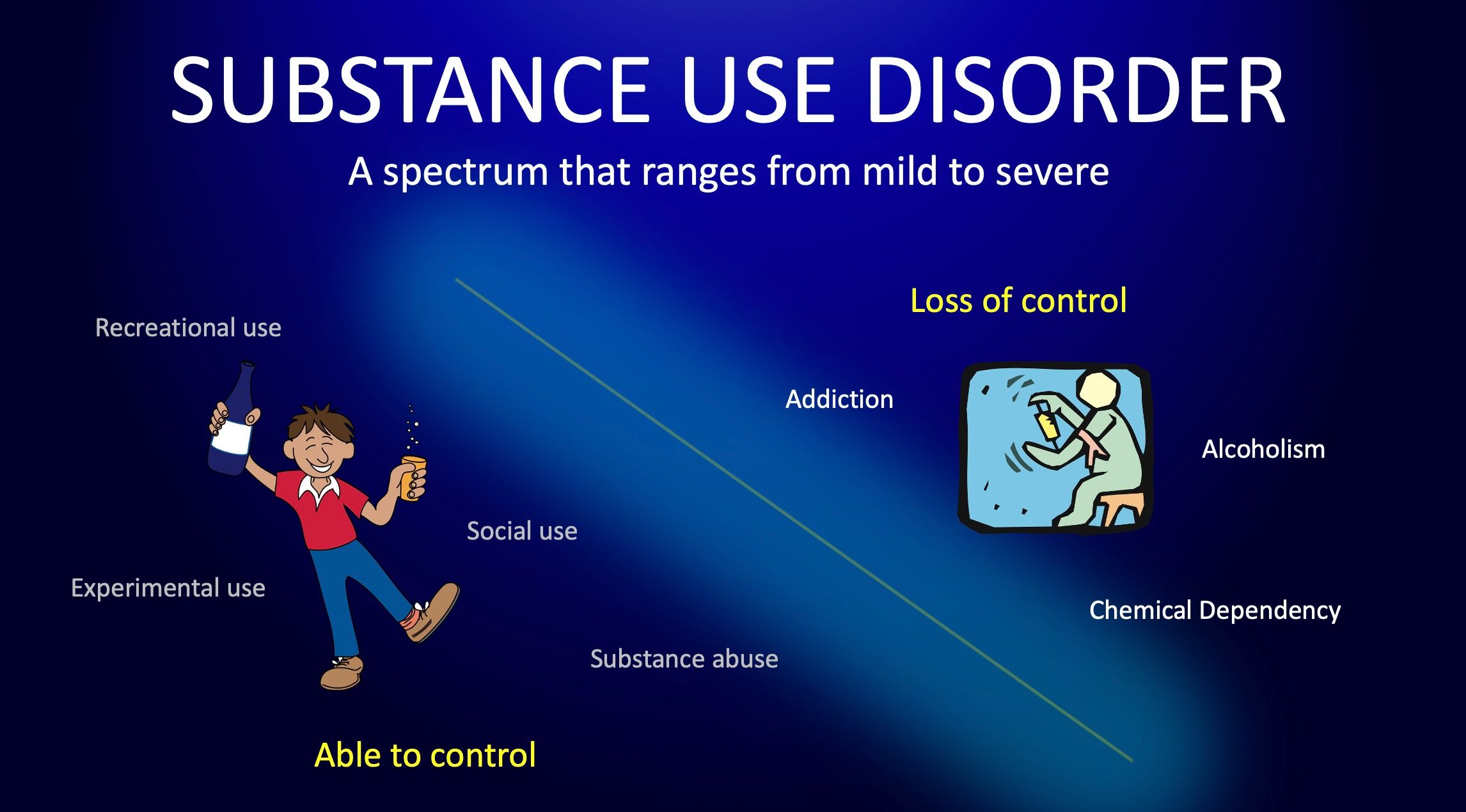

With so many terms floating around that refer to the various patterns of substance use that range from mild to severe (substance abuse, experimental use, recreational use, social use, chemical dependency, substance dependence, drug addiction, alcoholism, etc), what ends up happening is this sort of cross-pollination occurs. Like a bad game of telephone, people mix and match all these words and come up with their own definitions of what it means to have a "problem." And when it comes to intervention and treatment, there's a good chance that the client's definition, the family's definition, and the clinical team's definition of what it means to have a "problem" are all different.

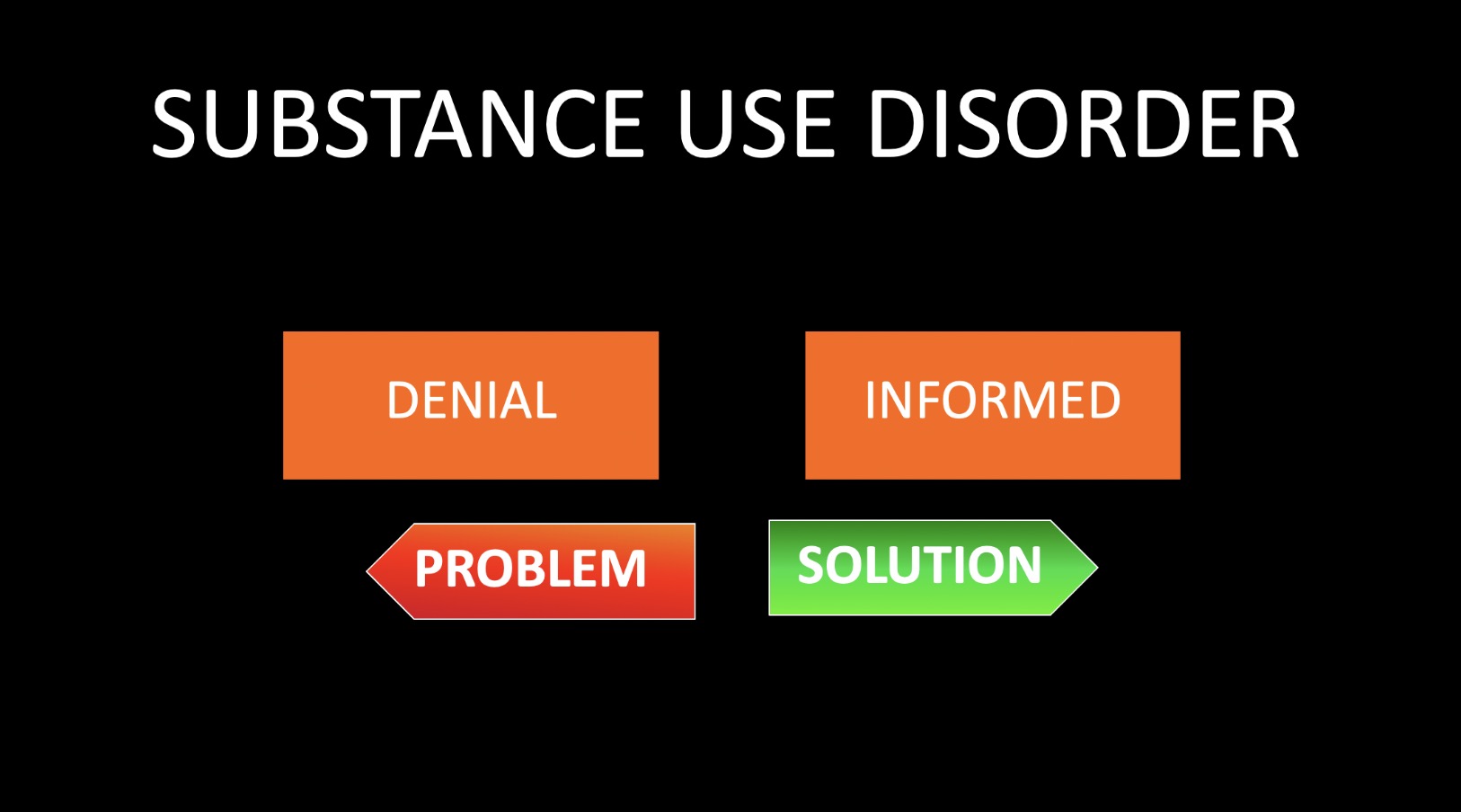

I led off my talk suggesting that as simple as it seems, this is perhaps one of the most overlooked reasons for poor treatment outcomes. The fact is many clients go through an entire treatment episode and never get past their own denial about what it means to have a problem. The family has their own thoughts about it, but they're not exactly sure what's right and what's wrong, what the treatment team says about it, or what they should say about it. And the whole treatment experience ends up being built on a dangerously unstable foundation.

The common denominator in all of the cases mentioned above is that substance use was clearly identified as an issue, yet it remained unresolved after treatment had been initiated.

Again, at the risk of overstating the obvious, the first step in effective prevention, intervention, and treatment involving substance use—especially in dual diagnosis cases—is getting clear about what it means to have a "problem."

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER

To cut through all the rhetoric about "problem" versus "not-problem," in most cases what we're really talking about is whether or not the individual in question has a diagnosable medical condition called Substance Use Disorder. That's the underlying awareness most people are referring to—even if they can't articulate it as such—when they're questioning whether someone's substance use is a problem or not:

"We're concerned she might have a problem."

"We definitely know he's using, but we're not sure if it's a problem."

"It's definitely a problem, but I don't think it's an addiction."

"We don't know if it's at the problem stage yet."

I'll suggest that what they're really wondering about is whether or not the individual has a substance use disorder.

Substance Use Disorder is a diagnosable medical condition. There are specific criteria a clinician uses to determine if the condition exists. If the patient meets the criteria, they have the condition. If they don't meet the criteria, they don't have the condition. At the risk of over-generalizing this, it could be said that this is the difference between having a "problem" or not. A person may use substances and not meet any of the criteria for Substance Use Disorder. This may very well be an example of not having a "problem." Again, I'm teetering on the edge of over-simplifying this, but I'm just trying to create some context here.

On the other hand, if a person does meet the criteria for a Substance Use Disorder diagnosis, then they've got it. From the perspective of "problem" or not, I'm going to suggest that this would qualify as having a problem. Implicit in the context of "medically diagnosable condition" is the understanding that if it's diagnosed, it needs to be treated. You can't overlook this.

"DISORDER" DOES NOT MEAN "ADDICTION"

It's important to note that when I say that having a diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder would qualify as "having a problem," I did not say they are "addicted." This is one of the first things we need clear up. A recent case I've been involved with provides a good example of how misperception can create a barrier to effective intervention. But it also shows how being informed about what it means to have a substance use disorder can actually be a motivating factor for becoming willing to address the issue.

I was contacted by the parents of an 18-year-old boy who had been concerned about the boy's cannabis use for over a year. When we were making the appointment for the initial assessment, the mother let me know he was resistant to meeting with me. Apparently his comment to her about having to see me was "He's just going to say I'm a bad person." Despite his reluctance, we began the work of addressing his substance use issue.

One of our first sessions included a basic educational presentation that focused on the difference between "social use" and what might be identified as a having a "problem." This included a discussion on Substance Use Disorder diagnosis. And in particular, I've found it extremely valuable to examine some of the major changes that have occurred in recent years as far as how we view Substance Use Disorder. I go into this in detail in the livestream presentation, but I'll take a moment here to give you a quick glimpse into what I'm talking about.

Most people have a general idea of a "line that you cross over" when it comes to addiction. And this breeds an either-or mentality: "I'm not an addict!" From this perspective, it's understandable that there might be some resistance to addressing the issue. I've discovered that an effective way to reduce that resistance is to begin with a little history lesson on how we used to diagnose Substance Use Disorder compared how we do it now.

The old framework supported this "either-or" mentality because there literally was a "line you cross over." On the mild side of line the client received a diagnosis "Substance Abuse." The severe side of the line is where the client would receive a diagnosis of "Substance Dependence." This was basically synonymous with "addiction." When I present this framework to families, they usually nod when they see this. It makes sense. It's how we've come to think about substance use issues. And it's how they're thinking about it at the moment. Most assessment clients don't want to be told they've crossed over the line.

However, I then throw them a curve by letting them know that what I just showed them was wrong! It's not how we view it anymore.

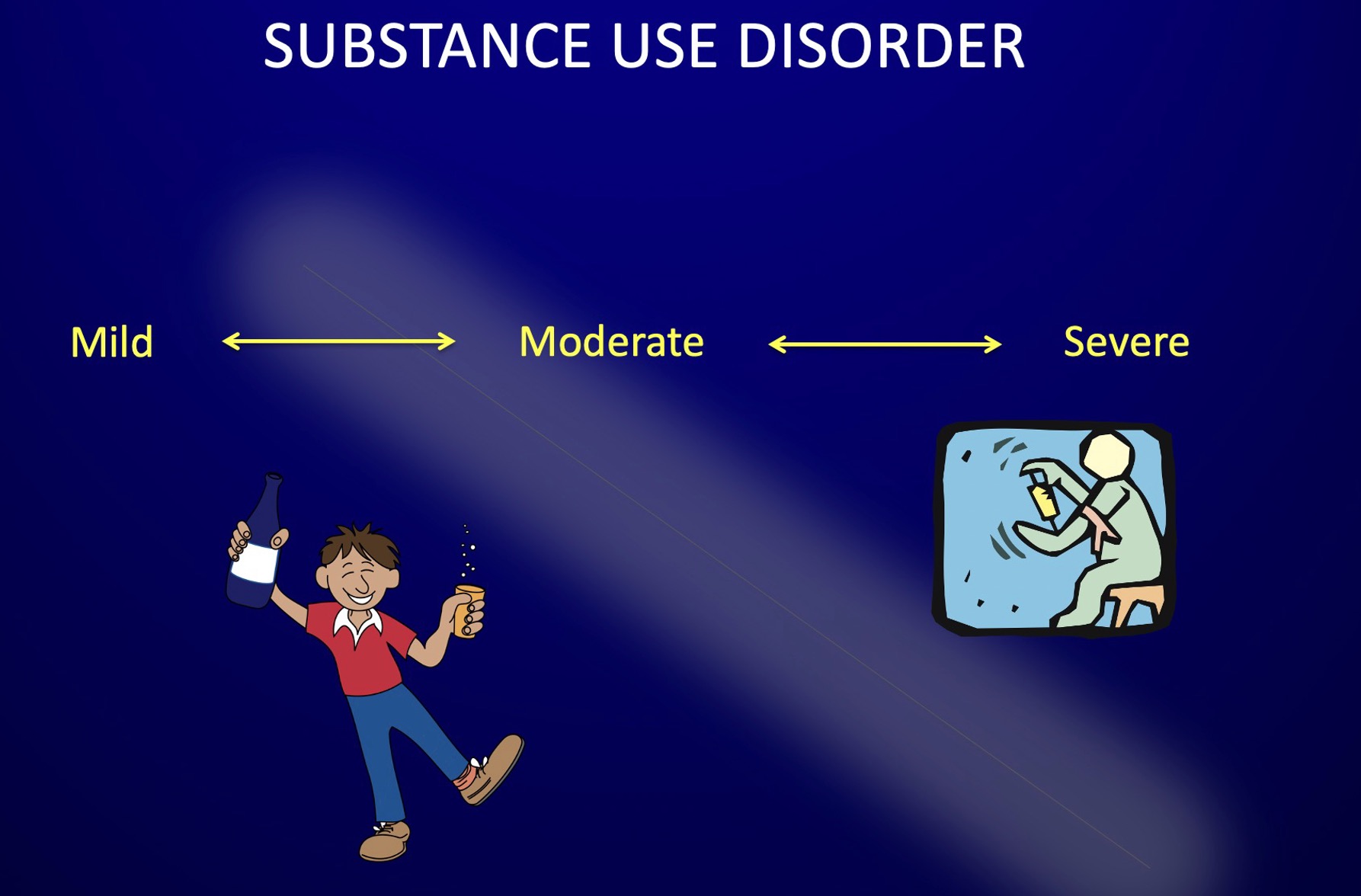

I proceed to show them the current framework and how this effectively removes the old black and white dichotomy of "you're either addicted or not." They did this by taking the line out and making it all one condition that exists on a spectrum. The diagnosis is now "Substance Use Disorder," with designations of "mild," "moderate," or "severe." This helps the client understand that while they may meet the criteria for having a "disorder," it doesn't automatically mean they are "addicted." And that's really valuable.

REMOVING THE STIGMA OF ADDICTION

The client in this case provided a good example of how explaining this can go a long way in helping them be more receptive to addressing the issue. At the end of this educational presentation I typically ask clients, "What was the best thing you got from the session today?" In this case, the boy's response was:

"I liked how you explained the part about it being a disorder, but it not being full-blown addiction. That makes sense to me."

As he continued, I began to understand what his mother meant when she said he was afraid I was just going to say that he was a "bad person." In his mind, I was the big bad drug counselor who was going to be tunnel-visioned on this idea of whether he has a "problem" or not. And he was sure I would land on the "has a problem" side of the aisle. The fact is he knows on some level that he does indeed have a "problem." But he also doesn't believe he's an "addict." And he's right on both counts!

A simple explanation of Substance Use Disorder diagnosis helped him understand how both of those statements can be true without being a contradiction to the other. But think about his statement to mom:

"He's just going to tell me I'm a bad person."

I'm guessing he was equating the possibility of being told he was "addicted" with being told he was a "bad person." From this perspective it's entirely understandable that he would be resistant to addressing his substance use. In his mind be was stuck between two conflicting positions: He knew on some level that he has a problem. But he didn't think he was what the professional was going to say he was. (Did you follow me on that one...)

Ultimately, he felt validated upon hearing "No, you're not addicted." But this also resulted in him being more open to addressing the issue because he was no longer feeling defensive about being saddled with a label he didn't feel would be warranted.

MILD, MODERATE, AND SEVERE

As stated above, Substance Use Disorder is a medically diagnosable condition that exists on a spectrum with designations of mild moderate, and severe. "Addiction" lives somewhere on the severe end of the spectrum. The important point to recognize when addressing substance use with teens and even young adults is that in many cases they haven't been using long enough to end up on the severe end of the spectrum. The reality is we don't see a lot of "full-blown addiction" with young people. However, an unfortunate irony is that I think this ends up being a major problem when it comes to addressing early stage substance use, especially when the substance use isn't identified as the presenting problem. (See: dual diagnosis)

And you don't have to look any further than the four examples I opened this article with to see what I mean.

I'm going to assume that the client in each of those cases would have been given a diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder at the outset of their respective treatments. (If not, there's your problem right there.) Most likely these all would have been specified as "mild" or "moderate." The critical point here is that even if it's not "severe" (as in, looks like "full-blown addiction"), it still needs to be treated.

The first thing we need to clarify is that "treating" a substance use disorder doesn't automatically mean "getting shipped off to rehab."

Residential or inpatient placement is usually indicated when:

- the primary diagnosis is Substance Use Disorder, severe (including need for medical detox)

- a mild or moderate Substance Use Disorder diagnosis is part of a dual diagnosis where co-occurring mental health issues dictate the need for an intensive placement.

The important point to recognize is that there is an appropriate way to treat Substance Use Disorder. And this is dictated by the severity of the diagnosis. The treatment plan for a mild substance use disorder is likely to be different than the treatment plan for a severe substance use disorder.

Unfortunately, what I see happening more and more frequently these days are cases like those above—where the substance use is not addressed responsibly, and in effect is allowed to fall through the cracks. My observation is that this tends to this happen more with the mild or moderate cases—because they're not severe! In other words, they don't look like "full-blown addiction," so a responsible treatment plan is never developed.

In my view, this is what happened in each of the cases above. And the results are tragic.

- A girl is expelled from school for using drugs her first day back from treatment.

- A frantic mother feeling deflated after eight weeks of wilderness therapy and finding out how woefully inadequate the substance use treatment plan was. Not to mention the dangerous circumstances the boy is currently in.

- The parents who paid for 90 days of residential care in a dual diagnosis program, only to be having to pay for another 90-day program a few months later due their boy's continued marijuana use. Not to mention the harmful impact of the unresolved substance use issue on family dynamics, interpersonal relationships, stress, etc.

- The counselor who informed the parents their son had a mild substance use disorder, and proceeded to implement an ineffective treatment plan as the boy continued to smoke marijuana daily while being "treated."

Clearly the responsibility begins with the providers having an adequate understanding of the implications a Substance Use Disorder diagnosis holds for treatment and recovery. And it's slowly occurring to me that perhaps a lot of mental health professionals just don't have a good understanding—or perhaps a better way to put it might be an appreciation, or respect—for what it means to have a Substance Use Disorder diagnosis, and more importantly, the implications this holds for treatment and recovery.

On the other hand, parents can't be expected to know what you don't know. But that doesn't mean you just sit back and do nothing. The entire premise behind my work with Rehab Works! is that the family has a lot more to do with treatment outcomes than most people realize, and there's a lot you can be doing—that's within your control—to dramatically improve your child's chances for treatment success.

(NOTE: A good place to start is by learning everything you can about exactly what we're talking about in this article. This all comes from my course called "Understanding Substance Use Disorder" which is a convenient way for parents to remove any questions or doubts about addressing substance use and appropriate treatment support. Look for info in the Resources list at the end of this article.)

DUAL DIAGNOSIS

As I alluded to above, a special note needs to be made with regard to the term "dual diagnosis." This refers to co-occurring conditions: A mental health disorder, AND a substance use disorder. And here's where I'm probably going to ruffle a few feathers. (Although I'm only trying to work together to help improve treatment outcomes!)

It's my observation that "dual diagnosis" treatment is where substance use most frequently falls through the cracks and leads to outcomes like the cases described above.

As already stated, I think there's a natural tendency for this to happen due to the fact that we don't see a lot of cases that look like "full-blown addiction" (severe SUD) with young people. But here's where we see why it's so important to be informed about Substance Use Disorder. The solution for avoiding this inherent challenge for dual diagnosis treatment lies in the simple points that have already been outlined here:

a. One can have a Substance Use Disorder diagnosis without being "addicted."

b. If Substance Use Disorder is diagnosed, a responsible treatment plan needs to be implemented.

c. The treatment plan is determined by the severity of the diagnosis; a treatment plan for a mild disorder is likely to be different than a treatment plan for a severe disorder.

A final point to be aware of is that Substance Use Disorder is identified as a primary condition. This means that other areas of the client's life that are negatively impacted by the substance use cannot be effectively addressed until the primary condition is arrested. For example, just as it doesn't make a lot of sense to treat cirrhosis of the liver with an active alcoholic, it doesn't make a lot of sense to do family therapy to discuss trust and communication issues while the client is still using. They may say they are committed to improving trust, but that goes out the window the next time they get caught in a lie related to their substance use. The primary nature of the condition makes it imperative to make sure that if Substance Use Disorder is diagnosed, it needs to be is addressed responsibly.

LEARNING FROM THE PAST

One of the things I went into during my talk was the story of how I ended up being so focused on using this understanding of SUD diagnosis as a foundational aspect of intervention and treatment. It involved a near disaster with the release of my book Rehab Works!, which I won't go into here, but I will share another example of how I use the "history lesson", i.e. the contrast between the old model and the new model as a tool for reducing resistance and increasing motivation for change.

I explain that another critical change that came with the new diagnostic framework has to do with what we would consider "characteristics" of addiction. We used to think of this as only being applicable in severe cases where the client is clearly in "full-blown addiction." However, the new framework acknowledges the potential for individuals anywhere on the spectrum to be susceptible to experiencing some of these characteristics—even if they're not in full-blown addiction.

Examination of the case of the girl who got expelled for smoking marijuana on her first day back to school would show that if treatment providers had addressed her substance use responsibly, they would have identified the potential for "loss of control." This is using when you tell yourself you're not going to. And it usually occurs when one is exposed to external cues that remind them of using. As such there would have perhaps been a discussion—maybe even an assignment to complete—about the potential danger of being around friends who use. That would be called relapse prevention planning—a standard part of responsible substance use treatment.

Evidently that didn't occur, and she ended up using as soon as she got around her using friends, even though she knew she shouldn't. She displayed loss of control, which we used to consider as only happening to those on the severe end of the spectrum—a characteristic of "addiction."

Another characteristic that used to be relegated to the severe end of the spectrum is "progressive." As in, "Addiction is a progressive disease." We now know that anyone on the Substance Use Disorder spectrum is susceptible to the progressive nature of the condition. The pattern or severity of use may increase, as well as the harmful consequences related to the use. Getting expelled was a worse consequence than she had previously experienced from her substance use. This would be an example of the progressive nature of her condition.

Here's the important thing to note about this case: This occurred for a client with a mild substance use disorder. (At least that was my diagnosis when I assessed her. As stated above, the parents never heard anything from her treatment program about her substance use diagnosis.)

CONCLUSION

For several years now I've had this growing sense of the need to call attention to the importance of understanding the basics of what it means to be diagnosed with Substance Use Disorder. As I've watched the evolving field of addiction become more complex and sophisticated, I've had this gnawing frustration that many of the problems I see around poor treatment outcomes stem from this very basic issue of not being clear about what the problem is that's being treated.

In this article I've tried to illustrate how this is especially challenging with younger clients who may have a diagnosable substance use disorder, but are still in the early stages of the condition. Compounding this is the fact that substance use patterns have been going through some significant changes in recent years. In particular, the changing landscape of cannabis use is directly impacting the profile of young treatment clients to the extent that we see a higher level of acuity and a genuine need for dual diagnosis treatment.

The point I want to stress is how important it is to make sure that early stage substance use is being addressed responsibly and not allowed to fall through the cracks—especially in dual diagnosis treatment. If substance use is identified, you want to be clear about the diagnosis and the treatment plan for managing it responsibly.

RESOURCES

VIDEO REPLAY > > Addressing Early Stage Substance Use: What's The Problem?

Watch the replay of my livestream talk where I go into much more detail on the various points from this article. (You'll also get to hear about the near-disaster that led me to being so focused on diagnosis due to the radical change that occurred with the publication of DSM5 in 2013.)

ONLINE COURSE: Understanding Substance Use Disorder

A convenient solution to clearing up any questions about what it means when we say that someone's drug or alcohol use is a problem. Addresses some of the most common areas of misinformation and denial around substance use including:

- Substance Use Disorder diagnosis

- Causes of addiction

- Marijuana denial

- Cross-addiction

- Treatment and recovery

PARENT SUPPORT: Family Coaching Package

Treatment consultation services for parents addressing substance use with teen or young adult children.

- Evaluation and Placement

- Case Management

- Parent Coaching

FREE eBOOK

Sobriety Doesn't Have To Suck!

A Guide To Finding Excitement, Renewal, And Spiritual Fulfillment In Recovery

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive news, resources, and updates.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

(We won't send spam. Unsubscribe at anytime.)